______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Radu Tîrcă and Ștefania Hîrleață are students at University of Architecture and Urbanism 'Ion Mincu', Bucharest. At present, they lead their theoretical research on the subject of thermal towns and diploma projects in Govora Baths under the guidance of Stefan Simion, Irina Tulbure and Ilinca Paun Constantinescu. As students, they won second prize and best student project in a BeeBreeders international architecture competition - Mango Vynil Hub, third prize in a Zeppelin national competition - Prototip pentru comunitate, as well as other mentions in other competitions.

Lavender Hill courtyard housing,

London, UK, 2021

Sergison Bates Architects

©David Grandorge and Danko Stjepanovic

An interview with Jonathan Sergison

The following interview was conducted via ZOOM in July 28th, 2023

by Ștefan Simion and Radu Tîrcă

SS

My initial thought was to begin with the early days, before starting the office and meeting Stephen Bates and Mark Tuff. How did you decide to go towards architecture? And maybe, you could tell us something about the architectural environment during this period.

JS

I always enjoyed art at school, painting and drawing, but it was only when I stepped into an architecture school I had a better understanding of what architecture meant and whether I really had an aptitude for it. And if I hesitated at all about what to study, it was between painting and architecture. I was accepted into art school, but I felt architecture was about more than personal creativity. I know this sounds grand, but I felt it could also be useful to society.

When studying for my A levels at school, between the age of 16 and 18, I'd been advised to take mathematics. I was told I needed it if I wanted to become an architect. I also studied art and history, which I've always been interested in. But those years of studying mathematics were horrible. I am quite numerate, but when it became more abstract, I really did not understand the subject or find it very interesting.

I applied to many universities in the UK, including the AA [Architectural Association] for the first-year course and had an interview with Tony Fretton. This first meeting was very memorable. There were maybe ten people in the interview commission, but he did all the talking. He left a very strong impression on me, so much so that I felt that if he was an example of what an architect could be, I wanted to be an architect too.

In the end, I couldn't afford to go to the AA at that point. I found that there was another art school in the UK that had a course in architecture, and that was Canterbury. It really suited me, and I felt that an art school was a good environment to study architecture. I liked being surrounded by painters and sculptors and graphic designers...

Studying in Canterbury meant that I wouldn't live at home in London, where I grew up, which seemed like a good idea, as well. Not that I had a problem with my family, I just felt I needed space. So that's how it began. Intuitively, I felt that this was the sort of thing I wanted to do. When I started studying architecture, it quickly became clear that I’d made the right choice. I know this can be construed as a lack of modesty but having entered the school with very low A level results, I did very well at architecture school.

Canterbury was a good place to start my education. At the time there was a tension between a re-evaluation of Modernism and the impact of Postmodernism, which was quite interesting. Figures like Aldo Rossi were discussed, Stirling was also very important to many of the teachers, and certainly to me as a student. James Gowan came and gave a lecture, which I remember fondly. I also met Florian Beigel as a guest teacher, who was a very important teacher at the North London School and subsequently became an even bigger influence on me and my generation of London architects. He was brilliant and supportive.

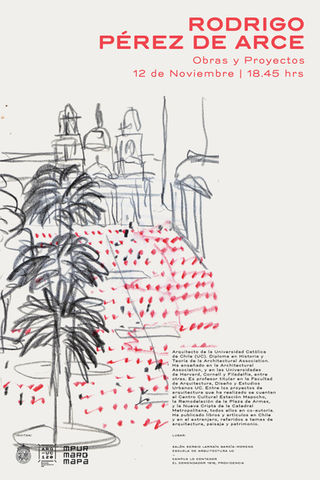

Then, after I graduated, I worked for David Chipperfield for a year, when his office was almost as many people as we are now on the screen [three]. And then I reapplied to the AA and was accepted again. There was one person there I really wanted to study with, Rodrigo Perez de Arce, and I was fortunate to do this for two years.

<<I applied to many universities in the UK, including the AA [Architectural Association] for the first-year course and had an interview with Tony Fretton. This first meeting was very memorable. There were maybe ten people in the interview commission, but he did all the talking. He left a very strong impression on me, so much so that I felt that if he was an example of what an architect could be, I wanted to be an architect too.>>

SS

That happened in the 80s, right?

JS

Yes, I started my studies in 1983 and I finished in 1989.

SS

So, you reapplied to the AA, and eventually studied there?

JS

Yes. I was at the AA between 1987 and 1989, when I graduated. As a school at the time, it was very competitive. I found it very stressful. I've never experienced the kind of stress I felt in the last year of my studies again in my entire career. It was a place of many egos and tremendous pressure and ambition. I'm not sure it was a very productive environment…

SS

From afar, it seems to emphasise a rather conceptual or experimental method, rather than a pragmatic approach. But I have not had the experience of studying there.

JS

I would completely agree with you. The reason I wanted to study there was Rodrigo Perez de Arce. He had been teaching there for 15 years. This was the period just before he went back to Chile where he was from. At the time he had a fascination for Iberian architecture. We went to Spain and Portugal twice with him. He was a brilliant teacher for me – and he still is, back in Santiago de Chile. We talked about building and situated the work within a wider understanding of the culture of architecture. That was unusual at the school then.

Later, in the 1990s, Mohsen Mostafavi invited me to teach in the school. He was a great educator and good head of school, in my opinion.

The cultural programme he brought to the school was all about building, and he gave a lot of attention to Swiss production, and figures like Marcel Meili and Roger Diener who both gave wonderful lectures. He curated an exhibition on Peter Zumthor, which included a lecture and a catalogue, and published a beautiful book on Peter Märkli, who was almost unknown at the time.

When he asked me to teach at the AA, I was quite young. I taught with Rosamund Diamond and Mark Pimlott. Afterwards, Stephen and I taught there for a few years, but it wasn't really such a pleasure. Somehow, there was a lack of generosity. There were some wonderful people in the school, and a few rather unpleasant ones. In time Stephen and I came to realise that there were better schools to teach the things that interested us.

SS

When did you meet Stephen Bates?

JS

I was working for David Chipperfield and Stephen had studied with him at the Royal College of Art in London. David was one of his tutors. When he graduated, David rather informally offered him a job, but he wanted to go to Barcelona, which was at the time a very interesting scene. Stephen worked there with Liebman Villavecchia for a year. When he returned, he came to the office, to see if the offer of a job was still a possibility. It wasn't, there wasn't much work at the time… But I remember Stephen coming into the office, and we started talking. I knew of someone that was looking to employ an architect and put them in touch. It was the beginning of a collaboration that is now 32 years old. It began with us meeting and talking, and at some point, agreed that it might be interesting to do a competition together.

SS

And that was the public house in Walsall?

JS

It was five years before that. It was a competition for an arts and crafts pavilion for a Welsh annual festival of culture, and it was the first competition we did together. To our utter surprise and confusion, we won it. While Stephen was quite happy to leave the office he was working for, for me it was a bit of a dilemma because I liked working with David Chipperfield and I knew I couldn't work on this project and work for David at the same time. Eventually, I took the bold decision to leave the studio, and did so on good terms. We worked on this project in Wales for a while and on other small projects.

Both of us felt that we weren't quite ready for practice. I did quite a bit of teaching at that time and still worked on and off for David Chipperfield and Tony Fretton. Stephen got a job and worked in a very professional office and learned a lot about building and contracts.

In 1995 at the encouragement of Tony Fretton, I instigated a series of meetings to bring together a number of people I knew in London. Every Sunday morning, we would meet in my apartment in Bloomsbury and talk about architecture. After a few meetings, what emerged was the ambition to make a journal. Each Sunday one of us would write a paper and present it, and the discussions were quite intense, questioning almost every sentence, which would mean the paper would need to be rewritten.

The people who frequently attended these informal meetings include Stephen Bates, Tony Fretton, Adam Caruso, Jonathan Woolf, Mark Pimlott, Juan Salgado, Ferruccio Izzo, Brad Lachore, Diana Periton, and David Adjaye. Looking back, they were some of the most interesting architects in London at the time. There were others, of course, practices like East and Muf, that I got to know later.

SS

How long did you have these meetings?

JS

We met for approximately 18 months, generally although not always, every week.

RT

And did Peter St John also come?

JS

No. Peter said that he'd rather be with his family on Sunday mornings and that was non-negotiable. Irene Scalbert attended once and upset Tony Fretton so much that the stool he was sitting on collapsed.

Unfortunately, I don't know what happened to the recordings we made of these meetings. They were on cassette tapes and got lost at some point, along with the papers. A few years ago, someone tried to print the papers, but it proved impossible to pull everything together. Stephen and I look back on this time quite fondly. It helped us to formulate our position and it was the beginning of our engagement with writing.

The most tangible output of the group was an exhibition at the Architecture Foundation, which at the time was in the Economist Building by Alison and Peter Smithson. It was rather improvised, but I think it was quite a strong exhibition.

You mentioned Walsall. I worked with Tony on his Walsall Gallery competition. Adam and Peter won it – and they later invited us to work on the adjacent public house, which was our first building.

us.

<<The people who frequently attended these informal meetings include Stephen Bates, Tony Fretton, Adam Caruso, Jonathan Woolf, Mark Pimlott, Juan Salgado, Ferruccio Izzo, Brad Lachore, Diana Periton, and David Adjaye. Looking back, they were some of the most interesting architects in London at the time. There were others, of course, practices like East and Muf, that I got to know later.>>

SS

To complete the image of your office, there's also Mark Tuff.

JS

Mark was the first person we employed. We formally set up the office in 1996. We had three small projects and a few months later, Adam and Peter asked if we would design the pub as part of the masterplan of the Walsall project. At that point, we knew we needed to employ someone. Stephen had met Mark when he was working in another office where he was an intern at the time. I remember Mark started working with us straight after finishing his diploma at the University of East London. He turned up for an interview with a few drawings in a plastic bag… And yes, he is now the third partner at Sergison Bates.

SS

Just a final question on how you work. As Stephen Bates teaches in Munich and you teach in Mendrisio, and you have two offices, I am curious: how do you find time to meet; how do you discuss the projects you have?

JS

Well, before I answer that, I should talk about how we worked in the first few years in practice, which might explain how things have evolved. We would work quite intensively on one project, as we normally only had one project on at a time. Stephen, Mark and I developed a method of working based on one of the many lessons we learned from Alison and Peter Smithson, the notion of ‘strategy and detail’, which we realized was an interesting way of developing work. From the outset we would agree a set of concepts for a project, and rather quickly commit ourselves to how it might be built. Stephen would produce drawing at 1:5 or 1:1. Mark would make the overall, general arrangement drawings, 1:100 plans, elevations and sections on the computer. He was the only one who could draw on a computer. I always was very happy working at 1:20 because it mediates these two scales, between strategy and detail.

That was how these first projects were developed and you can still see the hand of each of us in the drawings. Mark’s drawings tended to be printed from a computer and Stephen’s and mine were always hand-drawn. In time, more people joined the studio, we got more work and, certainly, there was much more computer drawing. We still draw by hand but not with the same intensity. We no longer ink drawings on tracing paper.

When I look at those early projects, I see how invested we were in developing a position as architects, a way of articulating our ambitions. I look at them now with great fondness, but I must admit it was fantastically inefficient, although very necessary, because we were really working things out. There was a lot of research, a lot of trying to develop ways of building that we felt were at the time sustainable and ambitious as forms of construction. Many projects dealt with the need to re-use existing buildings. From an architectural point of view, they were quite experimental. Also, we already had a great deal of interest in what was happening in other countries. We made many trips to look at other building cultures. Rather ambitiously we wanted to build as well as our Swiss colleagues, which, when you are dealing with the UK building industry, was, and remains, difficult to achieve.

In time, we came to realise that the intensity with which we worked on these first projects was unsustainable and not longer necessary. We had developed a shared position, and we now find it now more interesting to explore projects with more individual freedom. This means that there are differences in our work, although I am not sure this is so evident to the outside world. Naturally we all know what the other studios are working on, but not in great detail.

Stephen and I taught together at AA for years and later taught at Bath, ETH Zurich, and EPFL, and more recently in Oslo and Harvard. In 2007 I was invited to apply to teach in Mendrisio. Within a few months, Stephen also got a position in Munich. He has taught with Bruno Krucker, a Zurich-based architect, since 2009 and after teaching together for many years, it felt healthy to teach separately and explore our own individual interests. It must be said the programmes we set are not wildly different. Stephen is Professor of Housing and Urbanism, which is more or less what I teach in Mendrisio, too. I am Professor of Design and Construction and, more recently, I founded a new Institute of Urbanism and Landscape.

RT

ISUP [Institute of Urban and Landscape Studies - Mendrisio Architecture School], right?

JS

Yes, that’s right.

But to address the question of why we opened the Zurich studio –we were being invited to do more and more projects in Switzerland. We had a project on site in Geneva, and we decided it made sense to open a studio in Zurich. I was in Switzerland every week anyway, and at a certain point I felt that the studio needed more senior input. So I relocated to Switzerland with my family in 2012.

As with our teaching, this meant splitting the production of the studios. I am responsible for the Zurich studio and Stephen and Mark for the London studio.

I feel there are differences in the two studios because our work in Zurich is mostly based in Switzerland and responds to different circumstances, and slightly different interests. Most of the work in the London office is in Belgium. We also have a site office for the Kanal project in Brussels, but that relates to a specific collaborative project with NoAarchitekten and EM2N.

SS

You have touched the subject of teaching and I read about this in your very beautiful book, On and around architecture. Ten conversations. I really liked the straightforwardness of your first question, “Why do you teach?” Also, as we also teach, we often think about this. It takes up a lot of time and effort, and to be present in school is part of our identity as architects.

<<I think Stephen and I feel that teaching and practice are distinct activities, but they feed off each other. And the simple answer to the question why I teach is: not only because I really enjoy it, but also because I get a lot from it.>>

JS

I was drawn to teaching from a young age. Micha Bandini, who was a teacher at the AA and then became the head of school at the University of North London, invited me to teach with her. She said that she would help me learn how to teach, which is a most generous offer. Many schools have very young teachers who haven't had any experience or training. I find this problematic. In Switzerland this is not a problem, because teaching is quite hierarchical: there are students and student assistants, teaching assistants, and then professors. This is, in my opinion, a very pragmatic education model. As a professor now, I feel a responsibility to teach my assistants how to teach in the hope that one day they might become teachers, too.

I found myself teaching with Micha, who also invited someone I didn't know at the time, Adam Caruso, to teach with her. That's how I got to know Adam, who just seemed so brilliant.

I was in my late twenties when I started teaching, and after my first experience at North London, I taught in Nottingham and Hull. Later, I was invited to teach at the AA, and that was quite an education. I think Stephen and I feel that teaching and practice are distinct activities, but they feed off each other. And the simple answer to the question why I teach is: not only because I really enjoy it, but also because I get a lot from it. I give a lot of time to teaching, and I take it very seriously, but what I learn from teaching I would never find in practice alone. Responding quickly to an idea or a proposal that a student makes and trying to articulate a critical response that is useful to them and respectful - that’s not something you deal with in your own work. I've noticed that if I'm not teaching, I'm much slower as a designer.

Students bring things to my attention, and I learn from them. The students that I feel the most drawn to are always the ones that do brilliant things exploring their own interests. To some extent, my relationship to teaching is a bit selfish. I find that a way of working which includes teaching, practice, and a commitment to writing stimulating. It’s a triangle of forms of practice. And both Stephen and I are committed to all three, and to this way of working.

SS

Yes, I fully agree from my shorter experience of already 20 years. However, if you don't discover things

while teaching, it's a sterile activity to rather mechanically disseminate your certitudes.

Let’s turn to your architecture, and maybe discuss some theoretical aspects of it. For me, your architecture acts simultaneously on two fundamental levels: the room and the city [as in the title of Stephen’s last book]. It’s something we want to start this chapter with. I was wondering if you had any discussions or thoughts about where or what a room is. What is a room as a spatial entity, especially in this modernist approach of exploding the plan outwards and dissolving the box? The projects you have designed, from your earlier ones all the way to Hampstead, where the ‘society of rooms’ is varied and imaginative, have a rich genealogy in the spatiality of the room. There are so many types of rooms, and yet they're all the same, somehow.

JS

It's a very good question because it touches one of our core interests in practice, the making of rooms. I would argue that the room is not only an internal space, rooms exist in cities, as well. They exist in the public realm of cities, in terms of public spaces. The making of good rooms is one of our core ambitions.

Another fascination is making of windows, because they mediate between inside and outside, and the way windows are organized within a facade is an element of urban decorum. And yet, the window also serves the rooms, as it offers an outlook onto the city.

There's an essay by Georges Perec we both like, Species of Spaces, where he starts with a bedroom – actually with a bed, and then moves to the bedroom, then the apartment, the building, the street, and so on. It's a bit like the Eames’ Power of ten. What we have come to appreciate is an architecture that's made of rooms. The project in Hampstead you referred to explores that in quite a radical way. But, to some extent, it's indebted to a much older architecture. We have a certain fascination with northern Italian architecture from the 40s, 50s and 60s. The work of someone like Caccia Dominioni encourages and inspires our ambition in the making of rooms.

Our early projects were for social housing, where the space standards were horribly tight. The decision to have a corridor was a major one, because it doesn't help in terms of the overall square metres. So, I think that's part of a reflection about why we should make an apartment as a collection of rooms of different sizes. The pre-modern idea of making a home formed by a collection of interconnecting rooms is one we are drawn to.

The organization of plans is a core part of our work, particularly as housing is one of our main areas of investigation. But the plan doesn't tell you much about the spatial quality of a room. That's when you need to test spaces through models.

Both of us, in our different forms of teaching, invite students to record a domestic space and then make a model of it exactly like the photograph that they've taken, which is in turn photographed to record the space modelled. It's amazing how much we all learn from that experience.

We also learn a lot from revisiting completed projects. Whenever possible we like to see how spaces are inhabited and occupied by the residents. It’s not always easy, because at that point these are private homes, but when we have been able to revisit our work years later, we’ve learnt quite a few lessons. The way people arrange their furniture is nothing like the way the plans might have anticipated.

SS

There's a project in Bucharest by a photo artist, who went to one of these communist buildings, which are very repetitive. All the plans, from first to the eighth floor, are identical. He took the same photograph in each of the apartments which are of course inhabited, completely differently by each family. The variety of arrangements in the way identical spaces are inhabited was very striking.

You mentioned the facade, talking about windows and urban decorum. How do you feel about the modernist dogma of the sincerity in the relationship between the plan and the interior and how it should be represented to the city? In your opinion, do they still need to be true to each other? Or is there a certain freedom?

<<I am critical of modernist notions like ‘honesty’ and ‘truth of material’. in the long history of architecture, these were never so important. We like to work with ambiguity as a possibility in architecture.>>

JS

I remember a project by Tom Hunter, an English photographer, which was similar to the one you just described, where he photographed different apartments with similar plans in a tower block in East London. It reveals how much of the atmosphere and identity of an apartment comes from the choices the residents make in terms of decoration and furnishings – the point where our work as architects stops and that of the residents begins.

I am critical of modernist notions like ‘honesty’ and ‘truth of material’. in the long history of architecture, these were never so important. We like to work with ambiguity as a possibility in architecture. There is a very old building in England, Hardwick Hall, which dates back to 1590 and does exactly that. It’s a wonderful reference: from the outside it looks symmetrical, and the facade is formed from a lot of glass. When you look carefully, you see false floors behind the glass. The section and the tripartite organization of the facades are extraordinary. It is a building that demonstrates that you can give an impression of composition and formality, but then introduce devices that help you make adjustments to allow other things to happen.

While it’s very different, in a very early house that we built in Bethnal Green we used mirrored glass. We didn't want to reveal that there was a structural element behind the facade, and so we created a seemingly continued horizontal facade - it was a cheat. When modernists get all hot under the collar and talk about honesty, you have to ask, “is that interesting?” I think ambiguity and working with composition – this is where the artistry of architecture lies. I have never really been very interested in the notion of honesty in relation of construction. What does that mean for us, today? It’s not as if we're building solid masonry walls anymore. Contemporary construction is very layered. I think it was an aspiration or an ambition that quickly proved futile. And even if you look carefully at the work of Mies van der Rohe, which I still find really moving, he was above all a classical architect. He understood composition and proportion and really knew how to build, but he was invariably pragmatic, rather than seeking some form of purity.

SS

I would like to come back to the phrase you used: “urban decorum”. I was looking at your buildings and the attention you pay to how the facades are made, to a certain play of scales, and to the way the elements are articulated. Maybe it's wrong for me to use this word, but it comes across as a revaluation of the idea of ornament. Maybe the idea of room becomes even more powerful in your architecture, as the exterior is somehow dedicated to the city. So, is it wrong to use the word “ornament”?

JS

The notion of urban decorum is very important for me. I think that, over the years, our work has been described in many ways. “Ugly” is one that I certainly remember. I think I've read “quiet” in the past, which I'm more comfortable with. “Boring” I find the most offensive.

I think a lot about that and the fact that much of our work is housing. We feel that a building that serves the needs of housing should not be spectacular. It should be decent. It should feel solid. It should not feel like an imposition on the future users of the building. I don't think many people want to live in a house everyone looks at because it's so unusual. Housing should, by definition, be a noble backdrop. It should feel like it contributes to the city in a way that does not try to make a statement, or work in opposition to what happened before. I always come back to a wonderful quote by Roger Diener, about how one house can bring order to a place. When you know Roger Diener, you know that what he says is sincere. And it's what he's done over his entire career - his projects always consider the responsibility that comes from adding to a city. The fact that a building serves a more public role is always more of a challenge. You have to ask yourself how bold or how quiet a project should be. A public building is different to one that serves a more normative programme…

SS

It is, somehow, the autonomy of the facade and how the building addresses the city, which is, of course, essential: the meeting between the private and the public. I was thinking about how important it was for me when I discovered the idea of analogue architecture, Miroslav Sîk’s idea of a new building that seems to have been there for a long time – old-new.

I remembered this looking at one of your early projects, the twin houses. When I saw the project, I immediately thought, “how can a new building seem as if it had already been lived in for a long time. The notion of atmosphere is very important. I was wondering if it can become instrumental in working on a project. Is it something you can name or articulate or, somehow, design? Can you design the kind of atmosphere you are looking for?

<<In our work we are always searching for an atmosphere that fits the purpose, the presence of a building or an interior is at the core of our discussion. That is why construction is so important to us.>>

JS

In our work we are always searching for an atmosphere that fits the purpose, the presence of a building or an interior is at the core of our discussion. That is why construction is so important to us. If you choose to make something out of load-bearing brick, or from wood panels, the atmosphere of the interior will be fundamentally different. That's why I said earlier that to know what you want to build something out of is directly related to many decisions that follow.

It's great that you mentioned this early project – the twin houses in Stevenage – because we were exploring many things in that project. As Stephen reminded me recently, at the time we had a fascination with a photographic series that Dan Graham made, ”Homes for America’’, where he documented ordinary houses on the east coast of the States. The brief was to make two houses that touch, a pair of semi-detached houses or a double house. When we worked on that project, we made a sketch that imitates what a child would draw as two houses. Our conscious intention was to make houses that look ‘house-like’. That's why they have this almost naive kind of facade: it was the image of a house that we were exploring. And there were many, many other things in that project which we investigated: prefabricated construction, breathing wall construction, the notion of a layered form of construction, the use of Eternit tiles as a sort of fragile skin, how to achieve the abstractness we wanted the corners to have and traditional forms of construction wouldn't allow. It's a good example of everything that I was describing in the early years and the way we worked. We saw everything as an opportunity. At the time we didn't know Miroslav Sîk. Later, we got to know his students, people like Andrea Deplazes, Valerio Olgiati and Quintus Miller, who are now colleagues and good friends. And I also got to know Miroslav Sîk in time.

SS

Talking about atmosphere, I really enjoyed the anecdote that Stephen Bates remembered visiting the Wandsworth building with Andrea Deplazes, who noticed that two doors were not perfectly aligned by 18 millimetres and told you that in Switzerland, and in his office, it would have been designed to be precisely at the same height. I was thinking that this idea of tolerance and approximation is like an open work in the sense given to the term by Umberto Eco. Somehow, it seems that it is more a process of inviting people to inhabit your projects and contribute to the density of the place your work is part of.

JS

Yes, I remember that visit very well. And I remember feeling that somehow Andrea just didn't get it. His expectation of complete control of the building process didn't match our reality. Anyway, I still think that was more to do with his experience of how things are done in Switzerland, where there is an incredible control on construction. But is that any better? I mean, in Switzerland, you occasionally encounter works that are so uncompromising and so controlled... But they aren’t moving, they don't touch you. Olgiati’s work is very precise and very powerful. The work of Miller Maranta touches me in other ways…

I felt Andrea was being quite provocative when he saw that project. I also remember Marcel Meili, who just seemed to think he was visiting the Third World. He was so critical of everything. Martin Steinmann was much more charming when he went to see Seven Sisters Road under construction at that moment in the construction process where all the metal studs were set out and before the walls were plaster boarded. He just thought it was fantastic…There was something about the crudeness of the construction that he found exciting. It was quite a different reaction to those other visits to Wandsworth...

At the core of our conversations is the notion of tolerance, and we’ve written a lot about it and pleasure that comes from being both precise and imprecise. That’s why we like brick construction, because no two bricks are ever the same. The way that they are assembled has to do with the skill and the judgement of a bricklayer, it’s the work of hands. This is lovely, and it reminds me that construction is still quite low-tech and sort of wonderfully crude.

SS

I was in Lausanne for a year and a half. I studied at EPFL, and being there, I had the impression that the architecture in Switzerland and the architecture in Romania are, in terms of construction and budget, two different disciplines. We often talk amongst ourselves here, in Bucharest, about what the relevant references should be.

We are looking to Switzerland, even the UK and other parts of the world where the execution is superb, and everything is great. But then, when it comes to it, the real experience of a building site – on small projects, of course –seems much closer to the ideas of tolerance and improvisation. That is not the case for a Swiss architect who has everything worked out to the centimetre before the building goes on site. This is why I really love that. I think it's very specific and very true in the context of Bucharest. This might offer a more realistic idea about how to work.

JS

We work in so many different European countries now, and the first thing you learn to ask is what is appropriate and how buildings are built there? How can we make something conceptually meaningful without imposing a completely different building culture?” To do that can lead very quickly to a great deal of disappointment and, while I think it was true that when we first visited Switzerland, we came back with a determination to build carefully and a need for the elements of a building to be set out. There's a conceptual ambition at the heart of our work. Take, for example, our building in Geneva. If you tried to build it in the UK, you would be immediately disappointed, while in Geneva it was far from expensive in terms of building costs, and we could rely on a skilled building industry that could produce the precast concrete elements precisely. In the UK you would need a much bigger budget. In fact, something I have come to understand from working in these two building cultures is that the building costs are much higher in the UK than in Switzerland and quality is invariably inferior. I find your question absolutely pertinent.

You know that we have never had the chance to work in Romania. I hope one day I might because, of course, I have an emotional attachment to the country. What I always say is that to build is a huge responsibility. I’m always reminded of this when I'm in London, where so much building has gone on in the last 20 years, and most of it is so bad, and it will last… Well, it's not very well built, so it probably won't last very long, but even bad buildings do tend to last a long time. That's something that I fundamentally appreciate in Swiss society – the sense that, if one builds something, it should last for a long time, it should have quality. I think that's a very Swiss mentality, and it's quite different to the Anglo-Saxon attitude, which is more focused on capital returns than longevity.

If it is still possible to continue building –as we know that in environmental terms this is now in question – we need to be much more demanding about the quality of what is allowed to be built. We should, as a default, be trying to re-use buildings. I tell my students that, while I have had a career that has allowed me to build a few things, they should think about re-use in a creative and conceptually ambitious way. This is where their work lies, in ‘maintenance’, because our cities are already built, and we need to re-use what exists.

SS

I noted, before our talk, your ideas on sustainability and I really like how you put it in the terms of ‘intelligent building’. It is so common these days to talk about sustainability in technical rather than architectural terms, such as installing technical equipment to make a building sustainable. The idea of a building as a series of layers, some of which are very durable, have a long life and some of which have a shorter life span, and can be replaced. Architecture can then continue to be something that shapes the city. We find it very interesting, especially in the context of the school of architecture.

<<It's not just about one aspect, it's about everything being appropriate. It's about climate, place, economics, and the needs of future users, as well and the relationship between what is durable and what is more ephemeral.>>

JS

This notion of the ‘intelligent ruin’ is something Stephen is particularly interested in and the term is borrowed from the Belgian architect Bob Van Reeth. He argues that the most permanent part of a structure is the one that needs to be most carefully planned, considering how to allow for future re-purposing.

But sustainability has been something we've always discussed since our earliest projects. One can look at the ideas we were developing as a result of the need to build economically, not only in terms of capital investment, but as a holistic consideration. It's not just about one aspect, it's about everything being appropriate. It's about climate, place, economics, and the needs of future users, as well and the relationship between what is durable and what is more ephemeral.

SS

I think we are getting close to the end of our meeting. I wanted to ask you if you have been to Bucharest before?

RT

And you have been here with your students.

JS

Yes, we worked on Bucharest for one semester, you probably saw the projects on the studio website. It is a very important city in my life because I'm married to someone who grew up there. Bucharest often features in our conversations, some of Irina's family live there, and that's always a reason to visit.

I find it absolutely fascinating as a city because the urban character of the older city is particular to Eastern Europe. It is rich and, in my eyes, wonderfully different. You see so many different influences and qualities. It has a particular history that I find fascinating.

I hear the Romanian language almost every day, although I am ashamed to say I do not speak it. Romania is an amazing country, which I haven't explored nearly enough. My knowledge of it is limited to Bucharest, where I've been several times, and its surroundings. I've never been to the north. Culturally, I find it very diverse. After all, it's a very big country…

Thank you very much for this conversation. We’re looking forward to welcoming you here!

JS

I really look forward to coming back! It's been a wonderful conversation. And thank you both for your carefully prepared questions.

Bucharest, 1968,

George Serban photography

Botte House,

Bob van Reeth, 1968-1970